Stylos is the blog of Jeff Riddle, a Reformed Baptist Pastor in North Garden, Virginia. The title "Stylos" is the Greek word for pillar. In 1 Timothy 3:15 Paul urges his readers to consider "how thou oughtest to behave thyself in the house of God, which is the church of the living God, the pillar (stylos) and ground of the truth." Image (left side): Decorative urn with title for the book of Acts in Codex Alexandrinus.

Friday, June 30, 2023

2023 Trinity and Text Conference: How Has God Preserved His Word?

The Vision (6.30.23): Four Wondrous Attendant Circumstances at the Death of Christ

Note: Devotion taken from last Sunday's sermon on Matthew 27:50-61.

Jesus, when he had cried again with a loud voice, yielded up the

ghost (Matthew 27:50).

Following his account of Christ’s death on the cross (27:50), Matthew

describes at least four wondrous attendant circumstances that accompanied the

death of Christ in its aftermath (27:51-54):

First: The rending of the veil (v. 51a):

This event is also reported in Mark 15:38 and Luke 23:45.

The

“veil of the temple” here likely refers to the curtain which set apart “the

most holy” place (as in the Tabernacle, Exodus 26:31-33), or “the Holiest of

all” (Hebrews 9:3). This spiritually signified the opening up of a way or means

of communion between God and man through the mediation of Christ alone. Both

Matthew and Mark note that this veil was torn from top to bottom, indicating

that this mediation had to move from God to man and could not have come from

man to God.

Second,

the convulsing of the earth and the rending of rocks (v. 51b):

This

disturbance of the natural world is like the darkness which covered the earth

from the sixth to the ninth hour. Spurgeon says, “Thus did the material world

pay homage to him whom man had rejected….” (Matthew, 431).

Third,

the raising of some dead saints from their graves (v. 52-53):

Matthew

begins, “And the graves were opened” (v. 52a). He proceeds to record a most

unusual event, not covered by our other Gospels. He continues, “and many bodies

of the saints which slept arose” (v. 52b), adding, “And came out of the graves

after his resurrection, and went into the holy city (v. 53).

Note two

key things:

First,

though Matthew mentions this after the death of Christ, he states that this did

not occur until “after his resurrection.”

Second,

these persons did not experience the resurrection, but like Jairus’ daughter

(Matthew 9), the widow of Nain’s son (Luke 7), and Lazarus (John 11) they were

resuscitated, brought back to life to die again. Christ alone is the

“firstfruits” of the resurrection, and then all else at his second coming (1

Corinthians 15:23). Some of these saints (holy ones) might even have been elderly

disciples of Christ who had died just before he entered Jerusalem. They were

raised to bear witness to his resurrection power.

This

is the kind of miracle that modern, rationalistic, secularists might scoff at,

but once we affirm a God who had the power to make all things in the space of

six days and all very good, such things are mere child’s play.

Fourth,

the confession of the Roman centurion (v. 54):

Matthew

says the centurion (a man over 100 soldiers) and “they that were with him” witnessed

“those things that were done,” including especially the “earthquake,” and “they

feared greatly.” The centurion then said, “Truly this was the Son of God.”

Though

this confession was denied by the high priest (26:63b) and mocked by the

passers-by (27:40) and the religious leaders (27:43), a pagan Roman soldier

affirms what their spiritually blinded eyes could not see. Jesus is the Son of

God. The centurion represents myriads of Gentiles who will follow in his wake.

Grace

and peace, Pastor Jeff Riddle

Monday, June 26, 2023

Article: One Thing Is Needful: Exposition of Luke 10:38-42

Saturday, June 24, 2023

Friday, June 23, 2023

The Vision (6.23.23): The Cry of Dereliction

Note: Devotion taken from last Sunday's sermon on Matthew 27:39-49.

And about the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, saying,

Eli, Eli, lama sabachtini? that is to say, My God, my God why hast thou

forsaken me? (Matthew 27:46).

Just before Christ died on the cross (see v. 50), we read in v. 46

that he cried out in his mother tongue, “Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?” Matthew

translates for the Gentiles to understand Christ’s words, “My God, my God, why

hast thou forsaken me?” (cf. Mark 15:34). He is citing the opening verse of

Psalm 22. Some have called this the “Cry of Dereliction.” It is indeed a cry of

despair, like many of the Psalms of lament, such as Psalm 13, which begins, “How

long wilt thou forget me, O LORD?” (v. 1).

We should not think, however, that this is cry completely devoid

of hope, or propagate the unbiblical idea that the Father somehow “turned his

back” on the Son at this moment.

The Jews of the first century and the early Christians knew well

the Old Testament and especially the Psalms (cf., e.g., Luke 20:42; 24:44; Acts

1:20; 13:33, 35; Ephesians 5:19; Colossians 3:16). To quote but one line,

especially the beginning, was enough to call to mind the entirety of a Psalm.

This will cause us to look well at the whole of Psalm 22. Yes, it begins with

despair (see v. 1), but it ends with confidence and hope in God. See especially

Psalm 22:23-28. Psalm 22:24 even explicitly declares that the Father did not

hide his face from the Son: “For he hath not despised nor abhorred the

affliction of the afflicted; neither hath he hid his face from him; but when he

cried unto him, he heard.”

The cross did not take Christ by surprise. He knew he would be put

to death, but he also knew he would be raised. Review again the three passion

predictions recorded in Matthew, which are also resurrection predictions:

Matthew 16:21 (“and be raised again the third day”); 17:22-23 (“and the third

day he shall be raised again”); 20:18-19 (“and the third day he shall rise

again”). Add to this Christ’s statement following the Passover meal, “But after

I am risen again…” (Matthew 26:32).

He knew that all was in the Father’s hands, and, in the end, he

would have victory over death.

Grace and peace, Pastor Jeff Riddle

Wednesday, June 21, 2023

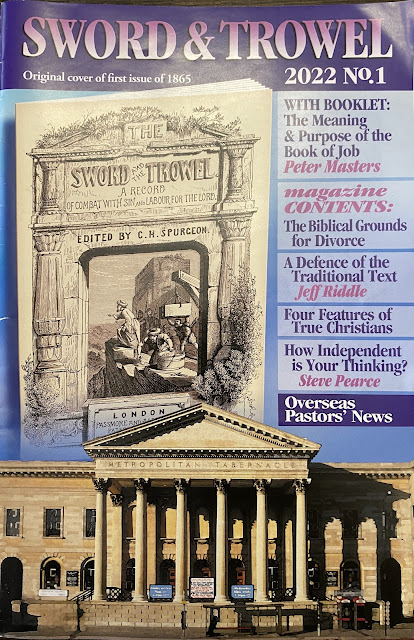

Article: A Defence of the Traditional Text of Scripture

I've posted to academia.edu a copy of my article, "A Defence of the Traditional Text of Scripture," which appeared in Sword & Trowel, No. 1 (2022): 9-18.

JTR

Tuesday, June 20, 2023

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.2.12: Concerning the words ascribed to John the Baptist

Notes:

In this episode, we are looking at Book 2, chapter 12 where Augustine addresses issues related to the veracity of the Gospel records in reporting the recorded speech of John the Baptist.

2.12: Concerning the words ascribed to John by all four of

the evangelists respectively.

Augustine here investigates how the reader might understand

statements attributed to John the Baptist in each Gospel respectively, while

harmonizing such statements overall as they appear throughout all four Gospels.

How does one, in particular, understand statements attributed to John that seem

to differ from one account to another? This discussion might be described as

addressing the question of whether the evangelists reported the ipsissima

verba (the very words), in this case of John the Baptist, or the ipsissima

vox (the very voice, but not the exact words).

Augustine begins with a discussion of how one differentiates

and recognizes direct quotation of speech. How does one distinguish between

something Matthew says and something John says when the text does not use some

clear grammatical indicator of direct quotations. He gives as an example the

statement in Matthew 3:1-3, which begins, “1 In those days came John the

Baptist, preaching in the wilderness of Judea, 2 And saying, Repent ye: for the kingdom of

heaven is at hand.” The question is whether or not the next statement in v. 3 [

“For this is he that was spoken of by the prophet Esaias, saying, The voice of

one crying in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make his paths

straight.”] was also spoken by John or information added by Matthew. In other

words, where does the quotation from John end? At v. 2 or at v. 3? Augustine

notes that Matthew and John sometimes speak of themselves in the third person

(citing Matthew 9:9 and John 21:24), so v. 3 might legitimately have been

spoken by John the Baptist. If so, it harmonizes with John’s statement in John

1:23, “I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness.”

Such questions, according to Augustine, should not “be deemed

worth while in creating any difficulties” for the reader. He adds, “For

although one writer may retain a certain order in the words, and another

present a different one, there is really no contradiction in that.” He further

affirms that word of God “abides eternal and unchangeable above all that is

created.”

Another challenge comes with respect to the question as to whether

the reported speech of persons like John are given “with the most literal

accuracy.” Augustine suggests that the Christian reader does not have liberty

to suppose that an evangelist has stated anything that is false either in the

words or facts that he reports.

He offers an example Matthew’s record that John the Baptist

said of Christ “whose shoes I am not worthy to bear” (Matthew 3:11) and Mark’s

statement, “whose shoes I am not worthy to stoop down and unloose” (Mark 1:7;

cf. Luke 3:16). Augustine suggests that such apparent difficulties can be

harmonized if one considers that perhaps each version gets the fact straight

since “John did give utterance to both these sentences either on two different

occasions or in one and the same connection.” Another possibility is that “one

of the evangelists may have reproduced the one portion of the saying, and the

rest of them the other.” In the end the most important matter is not the variety

of words used by each evangelist but the truth of the facts.

Conclusion:

According to

Augustine, when it comes to addressing “the concord of the evangelists” one

finds “there is not divergence [to be supposed] from the truth.” Thus, he contends

that any apparent discrepancies or contradictions can be reasonably explained.

For Augustine variety of expression does not mean contradiction.

JTR

Tuesday, June 13, 2023

Saturday, June 10, 2023

Friday, June 09, 2023

The Vision (6.9.23): Barabbas

Note: Devotion taken from sermon on Sunday, May 28, 2023.

Matthew 27:15 Now at that feast the governor was wont to

release unto the people a prisoner, whom they would.

16 And they had then a notable prisoner, called Barabbas.

17 Therefore when they were gathered together, Pilate said

unto them, Whom will ye that I release unto you? Barabbas, or Jesus which is

called Christ.

The Passover was a festival of liberation, remembering how

the Israelites had been set free from their bondage in Egypt by their savior Moses.

So, the release of a prisoner at this time seemed a fitting custom.

Even Pilate, a battle-hardened soldier known for his personal

cruelty and ruthlessness, could clearly see that the Lord Jesus posed no threat

to the common good. This custom seemed to pose the perfect opportunity, the

perfect loophole, to arrange the release of Christ from the penalty of death. Surely

the people would choose to free Jesus rather than another prisoner he held named

Barabbas.

He is mentioned in all

four Gospels (cf. Mark 15:6-15; Luke 23:13-25; and John 18:39-40), and we learn

more of him in the other accounts:

Mark

15:7 says, “And there was one named

Barabbas, which lay bound with them that had made insurrection with him, who

had committed murder in the insurrection.”

Luke 23:19 says of him, “(Who for a certain

sedition made in the city, and for murder, was cast into prison.)”

John says simply in John 18:40b, “Now Barabbas

was a robber.”

Even his name is spiritually significant.

Barabbas is an Aramaic or Semitic name, composed of two words.

First, there is the word Bar, which means

“son.” Peter was known as “Simon Bar-jonah” or “Son of Jonah” (Matthew 16:17). Maybe

you’ve heard of the contemporary Jewish practice of a Bar mitzvah, when

a Jewish boy is made a “Son of the covenant.”

Second, there is word abbas, which comes

from the word abba, which means “Father.” Mark tells us that when Christ

was praying in Gethsemane he cried out “Abba, Father” (Mark 14:36).

So, Jesus is the Son of God, and Barabbas means

“Son of the Father.”

In

the end the people chose to release Barabbas (v. 21: “They said Barabbas”). We see in v. 26a Pilate’s final decision: “Then released he

Barabbas unto them.”

We cannot overlook the

spiritual depths of this decision. The just and sinless man, the Lord Jesus

Christ, would go to the cross, while the sinful and guilty man, Barabbas, would

be set free.

It pictures for us

what will happen writ large on the cross. It pictures what the theologians call

the penal substitutionary death of Christ on the cross.

We are all Barabbas.

We were guilty sinners, deserving of God’s wrath, and we were set free, while

Christ, the sinless and just man, died in our place. In Romans 5:8 Paul says, “But

commendeth his love toward us, in that while we were yet sinners, Christ died

for us.”

Let us grasp hold anew today to the depths of the salvation that

is in Christ.

Grace and peace, Pastor Jeff Riddle

Thursday, June 08, 2023

WM 284: Eusebian Canons, Mark's Ending, Mark 15:28, & Luke 23:34a

Notes for this episode:

The Eusebian Canons:

In this episode I want to make a few brief comments drawn

from my recent reading through Francis Watson’s The Fourfold Gospel: A

Theological Reading of the New Testament Portraits of Jesus (Baker Academic,

2016).

As the subtitle indicates, this volume offers a series of

theological reflections on the four Gospels and their relationship to one

another. The author is a mainstream NT scholar at Durham University with whom I

certainly do not agree on everything, but the book still provides many helpful

insights.

One aspect of the book that is rather unique is the fact that

in the second half, Watson gives emphasis to how the Eusebian canons give

insight into ancient understandings and interpretations of the fourfold Gospel.

The Eusebian canons were composed by Eusebius of Caesarea (c.

260-c. 340), the “father of church history,” best known for his Ecclesiastical

History, and it was among the earliest attempts to provide a cross-referencing

system and a harmony among the four Gospels, long before the development of

modern printed Bibles with their chapter and verse divisions and in-text cross-references.

Eusebius had adapted his canons from an even earlier one composed

by Ammonius of Alexandria.

These canons appeared in mss. (Greek and versions) for about

a thousand years.

The canons are included in the front matter of the NA 28, along

with Eusebius’s Epistle to Carpianus (in Greek) which introduces the layout of

the canons.

There are 10 separate canons which group various passages in the Gospels along with their parallels. Canon I has passages that appear in all four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John); Canon II has passages that appear in the first three Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke); etc. The final Canon X consists of four sub-canons which list passages that are unique to each individual Gospel.

Then, in the text of the NA 28, references to these canons

are listed on the inside margin of each page with two numbers (top and bottom).

The top number provides a sequential reference for the passage and the bottom

number provides the reference to the canon where the passage is located.

It seems there has been a revival of interest in these canons

and in examination even of how they influenced early Christian reception and interpretation

of the Fourfold Gospel. Some are even giving credit to Eusebius and his canons

for solidifying the canonical consensus on the fourfold Gospel.

For a very recent work on this subject, see Jeremiah Coogan’s

Eusebius the Evangelist; Rewriting the Fourfold Gospel in Late Antiquity

(Oxford, 2023).

The Eusebian Canons and the Ending of Mark:

If you have ever done any research or study relating to the

traditional ending of Mark, you have probably heard as one of the arguments

against its authenticity is that it is not included in the Eusebian canons.

We know that Eusebius was well aware of controversy over the

ending of Mark. One key evidence of this is his Letter to Marinus in which he

discusses the fact that the ending is disputed by some. Interestingly enough, he

says that the source of the controversy had to do with harmonizing Matthew and

Mark with respect to the timing of the resurrection (Matt 28:1 “at the end of

the Sabbath” and Mark 16:2 “And when the sabbath was past” and Mark 16:9 “Now when

Jesus was risen early the first day of the week”).

This letter is the first hint of controversy over the TE that

lasts till c. 500. Clearly the TE was known from earliest times (see its

citation in Irenaeus’s Against Heresies).

So, the absence of the TE in Eusebius’ canons is given as an argument

against its authenticity, though it is ironic that these canons appear in

various Greek and versional mss. which nonetheless include the TE.

The Eusebian Canons and other disputed passages:

The thing that struck me in reading Watson is the fact that

he points out that the Eusebian canons make reference to several passages whose

authenticity is challenged by modern critics.

Here are two examples:

The

first is Mark 15:28 “And the

scripture was fulfilled, which saith, And he was numbered with the

transgressors” and its citation of Isaiah 53:12.

This verse is removed from the modern critical

text on the assumption that it is harmonization with Luke 22:37 “For I say unto

you, that this that is written must yet be accomplished in me, And he was

reckoned among the transgressors: for the things concerning me have an end.”

Watson points out, however, that Mark 15:28 is

listed in Canon VIII which shows parallels between Mark and Luke. So Mark 15:28

is listed as 216/VIII and Luke 22:37 as 277/VIII.

This is not to say that Watson accepts the

authenticity of Mark 15:28. He thinks it is “transplanted” from Luke (154).

Still, it is striking that the Eusebian canons are a witness in favor of

inclusion.

The second is Christ’s intercessory prayer in

Luke 23:34a, “Father, forgiven them; for they know not what they do.” I did a talk

on this passage last year for the TBS in London.

Watson points out that this passage is present in

the Eusebian canons listed as 320/X. He observes, “Although the passage is

missing from some early manuscripts and may be a later insertion, it was

present in Eusebius’ text and is identified in his analysis as a passage unique

to Luke” (156). Watson further notes that this prayer fits thematically with

earlier teaching of Jesus in Luke, including love of enemy (156).

Concluding Thoughts:

I was really intrigued by Watson’s insights on

what the Eusebian canons reveal to us about ancient understandings of the Gospels.

I am no expert on the canons, but I think it would

be interesting do further study see what other “disputed” passages appear in

the canons.

Given the information in the Letter to Marinus it

is unsurprising that Mark 16:9-20 is not labelled in the canons.

It seems, however, that the evidence from the canons

has not always been consistently used by some scholars and apologists. Though I

have heard many cite the absence of Mark 16:9-20 from the canons to justify a

verdict of that passage’s secondary nature, I have not heard those same

scholars make reference to the presence of passages like Mark 15:28 and Luke

23:34a in the canons to justify the conclusion that those passages are original

and authentic (though, as noted, Watson seems to lean that way with regard to Luke

23:34a).

Tuesday, June 06, 2023

Augustine, Harmony of the Evangelists.2.9-11: Harmonizing the Infancy Narratives

Notes:

In this episode, we are looking at Book 2, chapter 9-11where

Augustine addresses several points where some readers might see apparent

contradictions in the infancy narratives of Matthew and Luke.

2.9: An explanation of the circumstance that Matthew states

that Joseph’s reason for going into Galilee with the child Christ was his fear

of Archelaus, who was reigning at that time in Jerusalem in place of his

father, while Luke tells us that the reason for his going into Galilee was the

fact that their city Nazareth was there.

This brief chapter continues the discussion concerning

Archelaus which began in 2.8. Augustine harmonizes Matthew’s account of Joseph’s

fear of going into Judea given the reign of Archelaus, the angelic warning, and

the decision to go into Galilee (Matthew 2:22) with Luke’s account noting that Mary

and Joseph were originally from Nazareth of Galilee. He suggests that if there had not been fear of

Archelaus, they might instead have settled in Jerusalem, where the temple was.

2.10: A statement of the reason why Luke tells us that His

parents went to Jerusalem every year at the feast of the Passover along with

the boy; while Matthew intimates that their dread of Archelaus made them afraid

to go there on their return from Egypt.

Augustine must have known of some critics who saw the mention

of Archelaus in Matthew as somehow being at odds with Luke’s account on various

levels including the mention of the family’s frequent trips to Jerusalem.

Augustine notes that none of the Evangelists reveal how long Archelaus reigned.

Thus, he might have had only a short

reign. If it was longer, the family might have gone up stealthily, without

drawing notice to themselves. If this were the case, it only magnifies their

piety and faithfulness, despite these threats. Objections to the harmony of

Matthew and Luke are not insuperable.

2.11: An examination of the question as to how it was

possible for them to go up, according to Luke’s statement, with Him to

Jerusalem to the temple, when the days of the purification of the mother of

Christ were accomplished, in order to perform the usual rites, if it is

correctly recorded by Matthew, that Herod had already learned from the wise men

that the child was born in whose stead, when he sought for Him, he slew so many

children.

Augustine here tackles another perceived difficulty. How did

the family of Jesus go to the temple in Jerusalem for purification if Herod was

threatening his life? Augustine offers several explanations. One is that Herod

would have been too busy with other royal affairs to notice their visit.

Another is that he might not yet have been aware of the escape of the wise men.

Only after this purification rite was done and they escaped to Egypt did it

enter Herod’s mind to slay the innocents. Augustine even suggests Herod might

have been prompted to perform this evil act after hearing the publicity

relating to the words spoken by Simeon and Anna at the infant Christ’s visit to

Jerusalem.

Conclusion:

In these three short chapters Augustine suggests various reasonable

explanations as to how the birth narratives of Matthew and Luke might be fit

together into a unified and harmonious narrative. Armed with such explanations one

need not worry about any apparent conflicts in the story but receive them as

being in symphony with one another.

JTR

Saturday, June 03, 2023

WM 283: An error in Matthew 27:9?

In the end, Matthew 27:9 was not considered

a controversial matter in the days of early Christianity. As Metzger put it,

the traditional text was “firmly established,” and it raised no serious

questions about the infallibility of Scripture.

We can safely assume this same

pre-critical posture in our generation.

In the end, the most reasonable explanation as to why the reference is given in Matthew 27:9 to Jeremiah when the quotes which follows is taken from Zechariah, is the fact that Matthew and his hearers would have been accustomed to making reference to the whole of the prophets by use of the name Jeremiah as a reference to the whole corpus of prophetic writings.

Friday, June 02, 2023

Vision (6.2.23): Pilate's Wife

Note: Devotion taken from last Sunday's sermon on Matthew 27:15-25.

When he [Pilate] was set down on the judgment

seat, his wife sent unto him, saying, Have thou nothing to do with that just

man: for I have suffered many things this day in a dream because of him

(Matthew 27:19).

One of the unique details provided by Matthew in

his account of Christ’s passion is the reference to Pilate’s wife and the message

she sent to her husband in the midst of our Lord’s trial.

Notice four things about this:

First, she declared that the Lord Jesus is a “just

[righteous] man.” This is a reminder to any who read this account that Christ

had committed no actual transgression. He was not worthy of death in any sense

(cf. Rom 6:23 where Paul says the wages of sin is death; Christ committed no

sin; he was undeserving of death).

Her testimony of Christ’s innocence comes on the

heels of that of another unbeliever, Judas, who said to the Jewish leaders, “I

have sinned in that I have betrayed innocent blood” (27:4).

Second, there is an ironic contrast in that this pagan

woman sees and acknowledges something that the Jewish men who serve in elite

offices as chief priests and elders cannot see and refuse to acknowledge.

Third, she claims that her conscience has been

burdened, suffering all day about this matter because of “a dream” she

received. This is another ironic contrast with the Jewish leaders, because they

have the Scriptures and the all the things which the prophets wrote about Christ

(cf. 26:24: “The Son of man goeth as it is written about him”), but they do not

recognize him. All this woman had was an extra-biblical experience, apart from

Scripture, and yet she understood that Christ is a just man (cf. Romans 2:14-15).

Fourth,

she anticipates many Gentile women who will eventually come to recognize,

trust, and serve the crucified and risen Christ. Luke, for example, will say of

Paul’s ministry in Thessalonica, “And

some of them believed, and consorted with Paul and Silas; and of the devout

Greeks a great multitude, and of the chief women not a few” (Acts 17:4).

Grace

and peace, Pastor Jeff Riddle